There comes a time in the life of every municipalist when she’ll be forced to contend with calls to make the leap beyond local action. This demand may emerge after just a few months or it may take years but, inevitably, one day, people around her will start to say: “Municipalism isn’t enough. We’re hitting too many glass ceilings; our local government doesn’t have the powers or the budget to meet all our demands. We need to get into regional or national politics.”

I’d like to share some reflections on this debate, based on my experience as an activist in Barcelona En Comú and my observations of the strategies employed by other municipalist movements over recent years.

It is my contention that the drive to replicate municipalist projects at larger scales is seductive but ultimately dangerous. Calls to do so are often misleading with regard to the potential for transformative change at other levels. Worse still, they ignore the risks that expansionist strategies pose to the survival of the very organizations from which they emerge. Municipalists must heed the warning of the myth of Icarus, who tried to fly too high and fell out of the sky altogether.

Examining the supra-municipalist argument

In its purest form, the ‘supra-municipalist argument’, as I will call it, is based on two premises: first, that there’s a finite capacity for transformation at municipal level due to the limited powers and resources of local government and second, that replicating a municipalist project at larger scales is possible. The inference is that municipalists are obliged to create regional or national parties to achieve their goals. The argument is often supplemented by appeals to solidarity towards people in other municipalities and regions who have a desire to form part of a shared, transformative movement.

The challenge of limited institutional capacity at local level is indisputable and worth taking seriously. Even in Barcelona, a city with its own charter of autonomy and a healthy annual budget of over 2.5 billion euros, the Barcelona En Comú government has seen key policies frustrated by both the Catalan and Spanish administrations. For example, Spanish deregulation of the private rented sector and the Catalan government’s refusal to implement rent controls have led to spiraling rents in the city, which cannot be solved by the limited urban planning tools available to the local council. Similarly, the city has been unable to close the immigrant detention center within its administrative borders nor take in as many refugees as it would like because of the punitive Spanish immigration law.

In this regard, the call to ‘go beyond’ municipalism is particularly seductive for movements that have been successful at local level; after all, it is they who experience first hand the limits of municipal politics, even in the ‘best case’ scenario of being in government with strong grassroots support for their agenda. In such cases, what is there to stop a municipalist movement in its prime from setting its sights on the next rung on the institutional ladder?

Municipal vs. municipalist

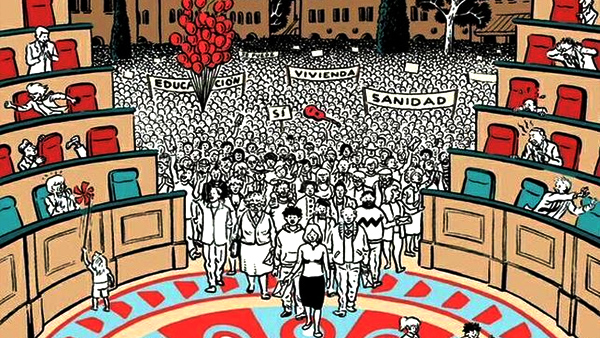

It’s here that we must question the second premise of supra-municipalism: that it’s possible to replicate municipalist projects – that is, those that are radically democratic, feminist and create new forms of collective identity – at larger scales. In order to do so, it’s worth recalling the municipalist hypothesis; municipalism doesn’t consist in merely ‘doing politics’ at municipal level, any more than feminism is concerned with the feminine alone. Municipalism understands that the local scale has characteristics that make it a unique site of social, political and ecological transformation and human emancipation. To quote the Murray Bookchin, municipalism “is structurally and morally different from other grassroots efforts, not merely rhetorically different. It seeks to reclaim the public sphere for the exercise of authentic citizenship while breaking away from the bleak cycle of parliamentarism and its mystification of the ‘party’ mechanism as a means for public representation…. It involves a redefinition of politics, a return to the word’s original Greek meaning as the management of the community, or polis, by means of face-to-face assemblies of the people in the formation of public policy.”

Municipalism seeks to harness the proximity between local institutions and communities to move towards direct democracy and the ‘co-production’ of policies, as opposed to the delegation of decision-making to elected officials and experts. It recognizes that the permeability between the private and public spheres at local level is essential to the feminization of politics and to placing reproductive labour at the centre of community life. Municipalism values the local sphere as the site for the production of collective identities that are based on civic participation rather than appeals to national or ethnic markers. This is vital if we are to move towards a world that is radically anti-racist and anti-colonial.

Anyone who understands municipalism in this way, as a process rooted in distinctive physical circumstances, and with the goal of reshaping society and challenging State power, will treat the claim that a municipalist political project can be just ‘scaled up’ and replicated other levels with at least a large dose of scepticism.

Look before you leap

Nevertheless, the question of whether a municipalist ‘leap’ to other levels is even possible, let alone desirable, is not one that can be answered by theory alone. Indeed, recent experience has shown that scaling up is at best difficult, at worst impossible or even self-destructive. I’d like to highlight some of the practical issues and related questions that municipalists should consider in any such debate.

One of the most important lessons we’ve learned in Barcelona is the individual and collective challenge of engaging in politics at multiple levels. As prosaic as it may be, every movement has a finite number of activists with a limited amount of energy and hours in the week. What is more, any movement that has recently entered institutional politics at local level for the first time will likely find its human resources stretched to the limit even before contemplating any multilevel adventures. Many municipalist movements and governments, at least in their early stages, are held together at the cost of sleepless nights, broken relationships, unpaid care work and a faith-like political devotion, all patriarchal practices that we should be seeking to ameliorate rather than reinforce. Before a municipalist organization contemplates setting up any larger-scale project, it must at least consider how both individual activists, and the organization as a whole, are going to manage this ‘doubling up’ of participation. Will it imply double the number of assemblies every month? Or will half of the time of existing assemblies now be dedicated to regional or national concerns? Currently the Coordination body of Barcelona En Comú dedicates over 20% of its time to topics relating to its participation in supramunicipal projects, while some neighbourhood assemblies have taken the decision to hold separate meetings relating to non-municipal matters. What are the opportunity costs of these decisions to the municipal project?

As well as placing a strain on resources, supra-municipalist projects can cause political tensions at local level. One of the great successes of municipalist platforms is their capacity to build broad local alliances. Local, goal-based processes are often able to mobilize and engage people from diverse political backgrounds and organizations even where national unity projects fail. This is thanks, in part, to the flexibility that local autonomy provides: it means that alliances and coalitions can vary from town to town based on local circumstances. In other words, the fact that a given party or political tradition doesn’t join the local municipalist platform in one municipality doesn’t preclude their counterparts from joining their local platform in another. Any larger scale alliance, therefore, risks straining or breaking municipalist platforms that respond to distinct local priorities, sympathies and logics.

The municipal level also allows people with different views on national politics to come together around local issues. For example, in Barcelona En Comú, people in favour of, against, and ambivalent about Catalan independence have been able to work side by side thanks to their shared municipal priorities such as increasing the public housing stock or remuncipalizing the water company. Municipalists should ask themselves whether there are national issues that are likely to generate disagreements and disaffection among local activists and whether this is a ‘price’ of multi-level participation that’s worth paying.

The third issue to bear in mind is one’s organizational and electoral capacity at other levels. Municipalist platforms that stand for election often do so after years or even decades of neighbourhood organizing, campaigning, learning and capacity building. It’s thanks to this critical mass in the streets that they are able to win elections and have the ‘thousand feet outside the institutions’ that are essential to changing the way politics is done. Given the human and political costs of setting up a regional or national project discussed previously, it’s important to evaluate carefully whether any new regional or national organization will be able to govern or be decisive in decision-making. For example, while Barcelona En Comú won the local elections of 2015, its national counterpart, Catalunya En Comú won just 8 seats in the Catalan parliament, a number far from sufficient to transform regional policy in ways that overcome the limits encountered by the city government. At the same time, it’s necessary to assess whether the structure of the new organization will be as porous, transparent and participatory as its municipalist counterparts. This is the only way to prevent it from turning into a traditional political party machine.

Finally, and most seriously, supra-municipalist projects can end up threatening the political and financial autonomy of the municipalist movements that create them. Traditional conceptions of territorial hierarchy almost inevitably mean that political positions adopted by the ‘higher’ body are imposed on its smaller, component organizations, while financial resources are centralized and used to service the interests of the national party. This is particularly problematic given the more limited and indirect forms of participation that are possible at larger scales. In other words, it is likely that a less democratic national party will end up having political and financial power over its more democratic municipalist counterparts, potentially suffocating their ability to maintain their transformative local agenda.

To summarise these theoretical and practical objections: there’s a significant risk that supra-municipalist projects, rather than allowing municipalists to ‘fly higher’, will fail to contribute towards the emancipatory goals of municipalism, distract valuable human and political time and energy from municipalist projects, threaten local alliances, have limited organizational or electoral success, and subsume their municipalist creators altogether.

Alternatives to hubristic demunicipalization

That said, objections to supra-municipalism must not imply complacency or a retreat to parochialism. After all, municipalism is valuable precisely because of its potential to challenge national and global political and economic dynamics, and Icarus’ father also warned him not to fly too low, lest the sea clog up his wings.

It is here that we come to the conclusion of the supramunicipalist argument: that municipalists are obliged to create regional or national parties in order to fulfill their transformative potential. In fact, there are a number of alternatives to this path. Leading municipalist theorists, from Bookchin to Ocalan, have advocated for a form of democratic confederalism, or networked municipalism, as a way of extending the territorial influence of municipalist values and practices. Bookchin described confederalism as: “a way of perpetuating the independence that should exist among communities and regions; indeed, it is a way of democratizing that interdependence without surrendering the principle of local control.” According to this philosophy, municipalists would do best by seeking to grow their movement horizontally by sharing and replicating their experiences in other towns and cities and driving cooperation and exchange at municipal level. The most fully developed version of this model can be found in Kurdistan, but it’s also being developed by Ciudad Futura (Rosario) across the province of Santa Fe, as well as by urban movements in Poland and Italy.

Of course, building bottom-up networks is a slow, painstaking process, and regional, national and European institutions aren’t going anywhere soon. It is my view that there is room for strategic action at other levels of government by municipalists, as long as it’s done with very specific goals in mind. When well-planned and executed, such action can have significant returns for municipalist organizations, while protecting them from the risks mentioned previously.

There are two models that stop short of creating a supra-municipal organization that, in certain circumstances, can be useful. The first is to establish strategic alliances with existing regional or national political actors. If there are parties with similar political goals at national level, it may make sense to support their election campaigns, collaborate with them on joint projects, or bring political demands to their door. Of course, this strategy won’t give municipalist organizations direct control or accountability mechanisms in relation to these parties, but it will allow them to support or pressure them from the outside, as appropriate, with a relatively small organizational investment and while maintaining their autonomy.

A second option is for municipalists to stand candidates for other levels of government as part of regional or national coalitions. For example, both Barcelona En Comú and Cidadãos por Lisboa have stood as part of coalitions with national parties in the Spanish and Portuguese general elections, respectively. While coalitions also suffer from democratic deficits in terms of accountability (each MP responds to its own organization of origin rather than to a shared ‘demos’), this model does at least give municipalist organizations a ‘foot in the door’ and direct control over their own MPs, who can use their position to put municipalist concerns on the national agenda.

Icarus’ sister

As I’ve already suggested, the supra-municipalist debate is deeply entwined with the issue of feminizing politics. A municipalist’s response to the call to enter into national politics will depend, in large part, on her willingness and capacity to question the patriarchal values of speed, size, hierarchy and dominance.

Protecting and nurturing our municipalist movements requires us to reject the idea that bigger and faster is better. Instead, we’ll have to accept our limitations (institutional, organizational and personal) and work around them, rather than against them. We must also resist the temptation to seek more institutional power if the cost is sacrificing real transformative capacity. Finally, it we must understand the growth of the movement in terms of horizontal collaboration rather than vertical control.

A healthy awareness that no-one is, or should be, omnipotent and an ability to prioritize as a consequence are essential ingredients of the feminization of politics and its reconciliation with human life. What would Icarus’ sister would do, if given wings of wax and feathers?